A lot of new CS grads have been noting that is really hard to get a job. I’ve personally been contacted by a couple people, including outside of Twitter, about the difficulty of finding a job. I’m sure if you’re reading this that you’ve heard some stories, too.

Here I will attempt to provide some insights as to what is going on. Basically, a massive confluence of factors has contributed to it being harder to get a job in tech, both on the demand and supply side of the market. I will cover all of these factors below.

Before I begin though, I want to be clear that trying to break into tech wasn’t always amazing. People familiar with my 2019 trying-to-get-hired saga will know where I am personally coming from. I’ll keep it brief: In 2019 I was more than qualified for an entry level data science role, but I struggled to get a “tech job.” I eventually got a “tech job” through a connection on Twitter, but it took a lot of trial and tribulation.

I only mention this anecdote so you don’t get the wrong impression about the recent past. They weren’t literally handing jobs away 5 years ago. That said, something has definitely changed and things are even harder today. Let’s dig into all the things on both the supply and demand side of the equation that are contributing.

The supply side: There are more CS grads than ever

I think this chart from the WaPo captures what is going on pretty succinctly:

Proportionally, CS majors are near mid-80s peak. If you account for the fact that there are more people attending college today than in the 80s, then it has peaked in terms of the total number.

It’s not just computer science majors either, but related majors have also surged in popularity. Basically, computer science majors have peaked in total and have near-peaked in proportion; when including CS-adjacent majors they are at an all-time peak in both totals and proportions; and humanities majors are at all-time proportional lows.

But why?

Pointing to these numbers explains the labor market supply increase, but begs the question of why there is a labor market supply increase. I have a few theories, but they’re just theories:

1. Word got out about tech jobs being good.

A lot of lot of young folks, deciding what to major in, finally got the message that was being pedaled for an extremely long time, which is that getting a job in tech is lucrative and great! Repeat “You can get paid a bajillion dollars if you work at Google” enough times, and people who want a bajillion dollars will take it seriously and perhaps reorient their college path around that plan.

2. The price of college changes the personal calculus

Growth in average student loan debt per student borrower has outpaced inflation for most of the last 15 years, which increases the opportunity cost of getting an un-lucrative degree in fields like the humanities. This pushes students toward more lucrative majors, such as in CS and CS-adjacent fields.

I’m not saying that college should serve as a training center for careers. There is a role that college should play in being a place of learning and in a place of personal discovery and comeuppance, separate of monetary considerations. But the more expensive college becomes, the more the opportunity cost of not pursuing a lucrative career in college increases. That’s just the reality of the situation.

3. Computers are cool now

Computer science may simply be more popular in a way that is orthogonal to students’ financial interests.

Technology has become a much larger part of people’s personal lives in the last couple decades, which can increase the salience and perhaps interest in the field: The possibility of working on the Instagram iPhone app is sexier, cooler, and more personally relevant to teenagers deciding their career paths than the possibility of working on IBM mainframes.

Whatever the reason, there are more computer science majors now than ever. If you are a new grad, this means you have more competition, all else equal. Except things are not all else equal. The demand side seems to be declining as well!

The demand side: Employers are hiring fewer software engineers

Again, a few charts to kick off the conversation. There are a lot of anecdotes about this, but I want to solidify that this is a real thing that is happening and not just vibes:

Indeed job postings:

Tech job layoffs:

Although a peak in job postings corresponded with a peak in layoffs, layoffs have continued at the same time that job postings have precipitously declined.

It’s worth isolating the “problem” with tech hiring from the demand side. The best numbers on tech employment in aggregate do not come from reading layoffs.fyi or Indeed graphs, but from the BLS. Overall employment for software developers is still growing ever-so-slightly, but growth has slowed down quite a bit in the past year and a half:

It should be clear when we talk about why getting a tech job is harder, we are not talking about there being some sort of tech recession; the numbers do not back that narrative up. When we talk about getting a tech job being harder, we’re talking about a higher difficulty of finding tech jobs specifically for new CS grads, which is not something that can be observed in the BLS employment data. (Anecdotally, the market still seems good for experienced software developers.)

But why?

The supply section is important, but sparse because the story is pretty boring: more people want tech jobs. The demand side is a little more interesting!

1. Interest rates

Interest rates are most likely the single biggest factor for why tech hiring has gotten worse.

The Federal Reserve has increased the target range for the fed funds rate starting in 2022, and the effective fed funds rate impacts interest rates across the entire economy, as a matter of risk premia: why lend at 4% to some business that might default, when you can get 5% risk free from the US government which has never defaulted and is unlikely to ever default?

It’s clear how interest rates impact mortgages and car loans, but what does this have to do with tech hiring? It’s complicated and multifacted, but I would point to three big mechanisms:

First, software tends to be something you pay for up front, and then make money on later. Meaning you need to go into debt first to make software. If borrowing money is more expensive, this means taking out loans to build software becomes more expensive and thus less desirable.

Second, higher interest rates make net present values more disproportionately skewed to shorter-time spans. Basically, when bankers calculate today’s value of future money, there is a simple formula to do that: NPV = CF / (1 + r)^t, where CF is a cash flow, r is the interest rate, and t is time (distance between today and the time of the cash flow). The higher r is, the more that a cash flow’s present value decays as t gets larger. You can calculate the derivatives, or better yet, just work with simple numeric examples:

- At r=0, the impact on NPV of a $1,000 cash flow is $1,000, regardless of how far out it is.

- At r=0.01, a 0-year out cash flow is $1,000, a 1-year out cash flow is $990, and a 2-year out cash flow is $980.

- At r=0.05, a 0-year out cash flow is $1,000, a 1-year out cash flow is $952, and a 2-year out cash flow is $907.

So naturally, higher interest rates push money-making decisions toward things that make money in the present, not things that make money in the future.

Third, low interest rates encourage more risk-taking behavior; high interest rates discourage risk-taking. Why invest in bonds that yield 0.25% when you can strike it big in equities? This is not my domain, so I may be wrong, but apparently the propensity to take on more risk during low-interest rate periods is not fully explained by nice economic theories that assume people are perfectly rational, so this necessarily involves some amount of human psychology to explain. Nevertheless, increased risk-taking when interest rates are low is a real empirical observation!

2. Section 174 of the tax code

Starting in 2022, the IRS has changed how software development can be deducted by businesses through Section 174 of the tax code. Software development is now an R&D expense, which means it must be amortized over 5 years (or 15 years for international hires) instead of deducted up-front. More accounting jargon here explaining the change.

Wait, isn’t that good? If I make $1m in revenue and my software developers cost $2m, I now made a balance sheet profit of $0.6m instead of a loss of $1.0m. Now I’m balance sheet profitable!

Yes, that is correct, but that’s actually bad for a software business! The issue is a business needs to pay taxes on the profits, but not on the losses. So by distributing the cost over time, this pushes businesses’ tax bills closer to the present.

The overall effect is that it makes software development more expensive to employers, especially in the short-term. To put this into perspective, the business Uber was founded in March 2009, so it is a 15 year company. Under the new tax code, the cost of an international software development hire that was around since the first few months of Uber’s existence will have only been fully amortized this year! 5 years is a long time in tech, and 15 years is a really long time in tech.

The only businesses not directly impacted by this are pre-revenue companies, since there’s no revenue to tax.

3. FAANG is hiring less

This may seem a bit like begging the question, in the sense that the question was “why companies are hiring less” and we’re answering by saying “because [specific companies] are hiring less.” But it’s not! Hear me out.

FAANG jobs are the golden ticket for tech employment; it’s where a lot of kids with really good grades at really good schools eventually go. For many reasons related to what we’ve already discussed, plus some reasons more idiosyncratic to the FAANG businesses themselves (e.g. how much more can Netflix grow its subscriber base from here, really?), they are hiring less. It’s also not just that they’re hiring less, but even P(interview|referral) seems to have dropped.

So where do all the kids with really good grades at really good schools go? They go to other inferior, non-FAANG businesses like Microsoft and Stripe (kidding! just kidding!), and the crowding out of that talent pool in turn impacts who competes for jobs at even less desired companies.

It’s probably not the case that “desirable tech jobs” is a fixed pie controlled by only 5 companies; we should expect that this equilibrium can adjust as long as demand for the byproducts of tech labor remains high. Still, a widespread redistribution of the tech talent pool can have some real short-term impacts as the market adjusts.

4. Hiring is hard now because lying and BSing has become more rampant

We’ll talk about this more in the second half of the post (*~✨~foreshadowing!~✨~*), but something that savvy people involved in hiring processes have caught on to is that there is more BSing and lying than seemingly ever in the tech hiring process. This is anecdotal, but I’ve heard about it from others on the hiring side and I’ve seen it for myself. [1]

This is more of a symptom of the labor market than a cause, and the effect it has is more redistributive of the pie (i.e. shifts jobs from truthful folks to bullshitters) than shrinking of the pie. That said, an honest person will experience this as a shift in demand, and there probably is a small effect on aggregate demand anyway as it increases the cost of hiring.

More on this in the next section.

“OK, but what about AI?”

Surprise! This is really a 2-for-1 blog post; two blog posts stacked on top of each other. The first part was about why tech hiring sucks right now, and the second part is to what extent tech hiring sucking has to do with AI.

I put all the AI related reasons in a special section because this is one of those hot button things that everyone is talking about.

People talk about AI in hiring like it is replacing engineers’ jobs. That is not happening right now, it simply is not and anyone saying that is bullshitting you. I also think it probably won’t happen for an incredibly long time (probably well after you retire, if ever), and I’ll explain why later.

That said, AI is part of the story, but in a much more interesting way than the dumb “taking our jobs” version of the story.

1. Venture money is flowing to capital-intensive AI projects

In a different era, when venture capital money was flowing to B2B SaaS or failed social media applications, this necessitated the hiring of a lot of hands on deck. You needed software engineers to build the B2B SaaS out, you needed sales people, and so on. Your non-labor costs were things like cloud and advertising.

In the wake of the AI craze, disproportionately more money is flowing to more capital-intensive projects. Pre-training an LLM requires a handful of people, sure, but most of that money an AI company raises is actually going to AWS, NVIDIA, and the many other service providers. Cloud spend for these companies will make up an even higher share of expenditures.

Personally, I question the wisdom of this! I’ve written about this before here:

In essence, these cooler things [i.e. training models] are essentially job perks, i.e. the perk of being able to have a little fun at work and grow intellectually.

And here (same post):

Algorithms are tiny parts of large systems. The algorithm part can usually be abstracted as an API call that provides some value(s) with inherent uncertainty; an ML endpoint is in essence an API call with few or no side-effects that returns an uncertain value. It turns out, the system design surrounding this almost always matters more than the algorithm and the dumb algorithms tend to do well enough anyway.

The generative AI equivalent of this is: I think if your product doesn’t work with an off-the-shelf model, it’s unlikely to magically start working with a custom, in-house model. This isn’t always true and it obviously depends on the nature of the product. (E.g. Midjourney would be uninteresting as a Dall-E wrapper, as part of the appeal of the product is its distinct style.)

But I think what I’m saying is true in a lot more cases than anyone wants to admit. And nobody wants to admit it because training models is fun and cool! You can have a good time and also put on your resume that you are a smart dude who put some JAX-based transformer model in production. Give a nerdy guy who pretends to understand verbose LaTeX math notation in arXiv white papers $100 million in a Series A funding round, and he will happily burn $80 million of it on GPU cloud compute doing stuff that doesn’t generate ARR.

Even if I’m right and that a lot of this money is being wasted, my rant doesn’t change the reality of the ground situation today. VCs have always dumped their money into burning fire pits with the hopes that the companies that 10x offset the returns of the companies that fail. The difference in 2024 is that this money doomed to incineration trickles down to data centers in Virginia, not to fresh-out-of-college CS majors. It’s capital intensive, not labor intensive. This is the real way today that AI is “taking your job.”

2. AI makes cheating the job hunt easier

Basically, LLMs are making it so that every text interface on the internet right now is being effectively DDoSed with garbage. Social media post spam and search engine spam are the 2 most salient cases where maliciously or recklessly generated AI “slop” is covering the internet in bullshit.

But wait, there’s more! AI-powered mischief has also encroached upon one of the most sacrosanct and unimpeachable of rituals performed on the internet: applying for jobs.

This is largely invisible to the broader public, but if you have been involved on the employer’s side of a hiring process lately, you may have noticed something was amiss. (See appendix [1] for my own anecdote relating to this.)

Basically, people are bullshitting! They are copy pasting the job posting into some LLM based tool and having it spit out some garbage. You can try it yourself. Find a job posting and copy+paste the requirements section into a prompt starting with: “I am a hiring manager. Provide an example of a resume that meets the following requirements:” or just keep it simple and do: “Can you extract a list of all the software tools required in the below job posting:” You can find Reddit posts with thousands of upvotes encouraging people to do stuff like this with links to tools that can assist in automating your bullshitting. You can even find dedicated tools with whole websites with the .ai domain that will do this for you, although I will not link them here as I find them viscerally reprehensible.

And the worst fucking part is that this works! It works because the top-of-the-funnel for hiring is typically handled by recruiters, and most recruiters are not super intelligent to be frank. They are behind the curve on the military-grade bullshitting that people are pulling on them right now. Recruiters also tend to promote very boring and cookiecutter notions of a successful candidate, so if you ask ChatGPT to give you a “good resume,” ChatGPT will output something with a very generic notion of goodness and it will also be the kind of resume that most recruiters will just so happen to consider their ideal. (Being a weird candidate with an unorthodox resume can be an advantage in many contexts, but for the pure raw numbers game of just getting a lot of first round interviews, regardless of the quality of the company you’re applying to, a boringly good resume is better than a weirdly good resume.)

A bad candidate who pulls this BS is going to fail a lot of technical screens, but they are going to get way more bites at the apple than honest, similarly situated candidates. And bites at the apple matter a lot. Sometimes the technical people cannot smell BS very well, or a company’s hiring function is more product-led than engineering-led so you’ll be more of a personality / culture hire. (Not that these will be amazing places to work, but they are tech jobs, regardless.)

AI is not actually taking your software job (and it probably won’t)

I find these conversations fucking tedious. (I’m not alone!) But it needs to be addressed because it keeps coming up. It’s an inescapable part of the discourse.

AI has not taken people’s software engineering jobs. This is just not happening. It isn’t. Nobody in their right mind has replaced their engineers with Devin because that’s just not a thing you can do.

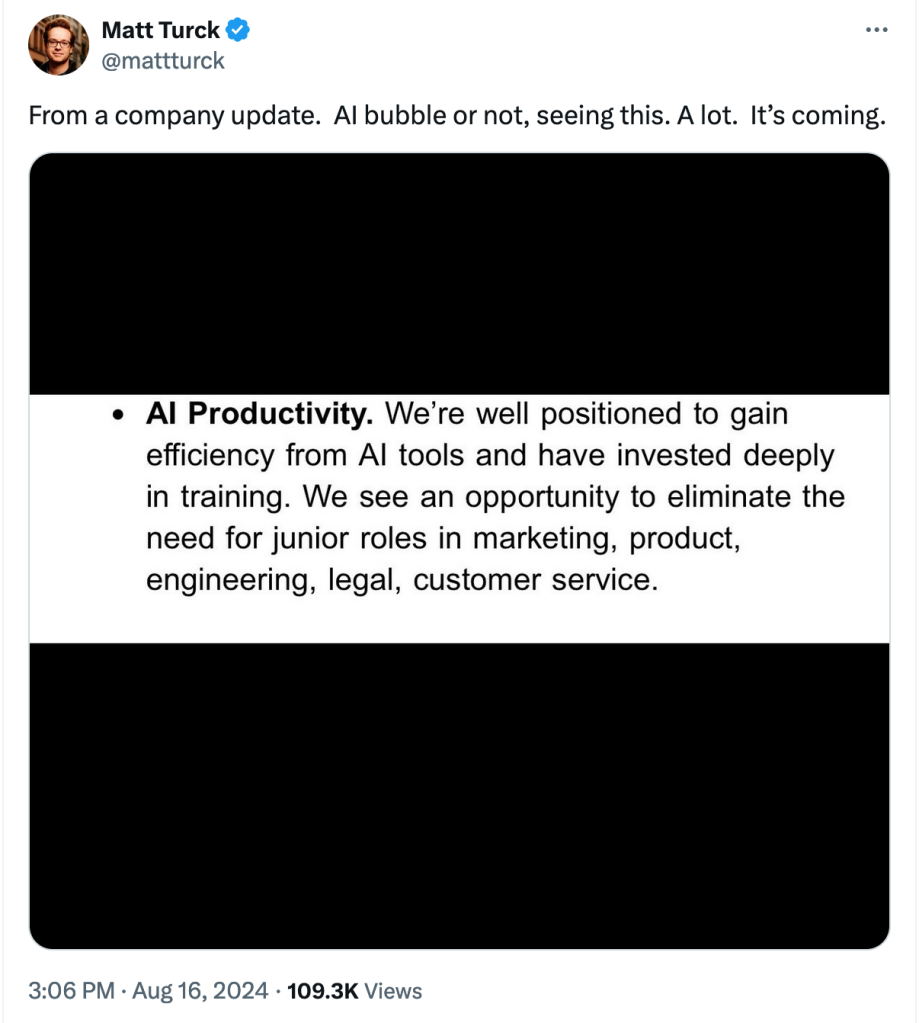

Here for example is a VC who believes everything his portco CEOs are telling him about AI progress:

Either one of two things is true:

- These companies are lying to him (either the CEOs are lying, or someone below the CEO lied to the CEO and it gets regurgitated up the chain).

- These companies are run by fools (either they are terrible at hiring competent/useful junior employees, they are terrible at making junior employees work on productive tasks, or they foolishly believe that an AI which won’t replace their juniors actually can replace them).

For Matt’s sake, I hope he is merely being lied to and not investing in incompetently run companies.

Just try using Claude or ChatGPT yourself to write code. You don’t need to take these companies at their word. Do you seriously think these things in their current state are ever replacing you? Do you think they’re even that close?

Do you think that these Series A companies with 50 employees saying they “see an opportunity to eliminate the need for junior roles in […] engineering” have access to some super secret AI tech that you don’t have access to that would vastly improve their internal capabilities, compared to what you can get out of a publicly accessible AI? Do you think it’s more likely that they are seeing something completely different from you due to their incredible internal capabilities, or that they’re seeing the same thing but they are just terrible at assessing it (or lying)?

Do you believe the people who act as if there are super secret magical prompting incantations to make the AI actually productive and useful, that you just cannot figure out because they’re prompt engineering pros and you just don’t know the correct incantations?

I highly, highly doubt any of this!

We’ve been through this hype cycle before with machine learning. Companies claimed to rely on super sophisticated machine learning and data science internally, when like 90%+ of these companies were at best exaggerating and at worst lying about not only impact but even the implementations themselves.

Not only is AI not replacing you today, the fantastical bull case of AI achieving sentience and building everything for you is nowhere in sight. It is not. Nobody knows how to achieve this! Anyone who says they know is lying! ASI has been 3 months away for the last 3 years, always based on bullshit rumors about some cryptic message an OpenAI employee said which ended up being a nothingburger. People who say ASI or AGI is around the corner are lying to you. Recent (last 3-4 years) developments in LLMs are impressive as is, you don’t need to lie about it. [2]

To the extent AI has been credibly attributed to layoffs, it’s more like Apple reorging Siri employees, Amazon laying off Alexa employees, Intuit laying off miscellaneous employees, because leadership deemed LLMs with RAG more suited to the tasks that Siri and Alexa are attempting to achieve and they want to move to LLM-based technologies. That’s a different thing from the AIs literally replacing the jobs!

It is telling the people who say this shit don’t even seem to believe it. Chris Paik, the guy who went semi-viral for posting a Google Doc titled “The End of Software,” is a software VC at a small shop named Pace Capital which led a $50mm funding round in March 2024 in a company whose main product is a Chromium-based browser, with (estimated) 100x fewer users than the browser Opera, but a post-money valuation only 2x less than Opera’s public market valuation. Does this sound like a man who believes the future is software that is trivially commoditized? The man isn’t even talking his own book, he is just talking.

In a world where AI is productivity-enhancing, I find it more likely that LLM-based tools will end up increasing productivity of junior software engineers and thus make them more enticing to hire. Yes, they may spend less time on certain tasks than before. But that just means the nature of the job function changes, it doesn’t mean junior engineers just poof and go away and never get jobs ever again. Did the development of high-level, easy-to-use programming languages like Python decrease jobs because you don’t have to wrangle with C to write some scrappy script? Obviously not. If people did all their data science in C, there would be no data science field of which to speak because there would hardly be any data scientists. Tools that make coding easier make coding more accessible to more people; they make coders more productive, and like magic, this means somehow more of them exist and more of them get hired to do more things.

I also do not believe there is a fixed or near-fixed quantity of tech work to be done. Any company with a massive backlog can attest to that. There are organizations out there which are so behind on their tech (government and healthcare sectors really spring to mind) that a credible promise of much more productive employees could entice them to get more shit done.

Are there reasons to worry about the impact of AI on software engineering? Eh, maybe, but I doubt it. [3] I am more bullish than bearish! But gainful employment is probably not a thing you need to worry about. AI is not currently taking software jobs, and I really doubt it will for a really really long time.

Negative forecasts of an AI-led decrease in aggregate employment (e.g. Andrew Yang, the fringe 2020 presidential candidate), outside of the tech sector, are even sillier. Productivity enhancing technologies can shift jobs around sectors (e.g. farm employment in the 18th century vs farm employment in the 21st century), that is for sure. But are there any example of a productivity enhancing technology decreasing jobs in aggregate? No, because that’s not how aggregate demand for employment works. People change jobs and the economy shifts. There’s always stuff for people to do, and if you’re a reasonably smart and competent person who knows how to code, you’ll be fine! (I realize that my tangent about AI may have, by coincidence, led to a salt-in-the-wound kind of way to end an article titled “Why does getting a job in tech suck right now?”)

Appendix

[1] Sometime in the last year, I helped with hiring a data engineer for a remote-friendly, hybrid-preferred role. We got a deluge of applications. This was somewhat expected, as we’d known the tech labor market was tightening.

The manager of the data team said, OK the job will involve a lot of Airflow, so let’s filter out all the people who don’t mention Airflow in their resumes. (This was not my decision, and I pushed back against it for reasons I describe here.)

Uh oh, this only filtered out about 1/3 of the candidates. Let’s start looking at the resumes more carefully. Hmm, a lot of people seem to meet all the requirements in the skills section of their resume. It’s not like our stack is esoteric, and we’d expect some self-selection bias (people who are familiar with our stack will be more likely to apply), but this is a little too good to be true.

Wait a gosh-darned second, a pattern is starting to emerge the more you look at these resumes. People are all mentioning that they know all the tools in our stack, but the relationship between their alleged experience with these tools and their actual job experience appears tenuous-at-best! 🤨 It is impossible to classify which exact resumes were BSing, but it definitely felt that in aggregate, at least some of them (perhaps more than just “some of them”) were BSing.

[2] My read on the situation, for whatever it’s worth: The main bottlenecks to improving LLM performance architecturally speaking relate to the fact that the objective function used to train LLMs (predicting words) is not how humans actually evaluate text (semantic content); and that coming up with a general objective function for all text is actually really hard and nobody knows how to do it.

Text is not like chess or go or Starcraft or Dota 2 where you have a clear objective function (win the game) and where you can train the bots against each other beyond the corpus of human-generated samples. E.g. a chess bot can start on Magnus Carlsen and Bobby Fischer games, and exceed their abilities by playing against itself a billion times with the clear objective of winning games. What is the text generation equivalent of that? Nobody knows. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Having one LLM try to hide a secret phrase from another LLM is the closest we’ve gotten to where an LLM can self-train on some sort of objective, game-like criterion. It’s a cool and clever design! I give props to the researchers for coming up with it. My priors lead me to believe it should improve LLM performance, not unlike how training a chess bot against another chess bot makes them super-human at chess. This design also has yet to achieve AGI or ASI, and it may still have serious limitations on improving performance because text is not quite chess. I know what a bot playing a billion games of chess accomplishes (assuming the bot has the objective of winning). What does a bot playing a billion games of don’t-say-the-magic-word accomplish? ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ Uhh, probably something? But unclear exactly what! It might just get really good at hiding secret phrases, and that could be mostly it!

[3] My worst case worries for the medium-term future of software development lie less in there being literally no jobs, and more in like, large subsets of future generations of software engineers being worse at software because they rely so much on AI that they never learn it, not so much that their jobs will go poof.

That said: previous generations would have said the same thing about moving from assembly to C or from C to Python. As I age, I will become more curmudgeonly toward things I didn’t grow up on, as I continue to use technology that prior generations were once curmudgeonly toward. But, I do believe that using an LLM to write code for you is a fundamentally different high level abstraction compared to a programming language that manages the memory for you and uses dynamic typing and what-have-you. Whatever. I really honestly don’t think it is that big of a deal!

Moving from “worst case” to “modal case” forecasts of the medium-term future: I think the most likely impact is that the AI doesn’t make the best developers worse (or, frankly, much better), but that it turns a lot of non-developers into bad developers. So you may see an average decrease in developer quality, but that this only occurs because the pool of developers got bigger, not because the top of the distribution shifted down.

You must be logged in to post a comment.